The Rumours Before the Storm

In the summer of 1981, whispers from across the Atlantic began to reach Amsterdam’s vibrant gay scene. News reports spoke of a mysterious and aggressive 'gay cancer' striking down young men in New York and San Francisco. For many in the Netherlands, it felt distant, an American problem. But for doctors like microbiologist Roel Coutinho, then at Amsterdam’s GGD (Public Health Service), a sense of dread was setting in. The storm was coming.

Robbert Blokland en Matthijs le Loux:

Live to tell. Het verhaal van hiv en aids in Nederland

By 1982, it had arrived. At the Academic Medical Center (AMC), internist Jan van der Meer was confronted with a patient named Dick, a flight attendant who was wasting away before his eyes. He was covered in purple spots—Kaposi's sarcoma—and his lungs were failing from a rare pneumonia. "We had no idea what it was," van der Meer recalled. "We stood by, watched, and our patients died. There was nothing we could do."

A Community Under Siege

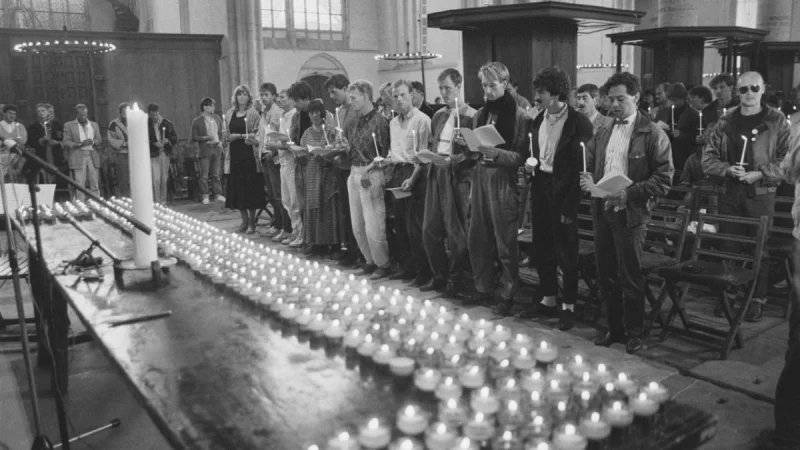

The disease, soon to be known as AIDS, tore through the community with terrifying speed. It was a plague that seemed to target gay men specifically, turning bodies against themselves. Fear and paranoia gripped the city. Young, healthy men were suddenly faced with a death sentence, their lives cut short by an invisible enemy. The medical world was powerless, able to offer little more than comfort as patients succumbed to a cascade of opportunistic infections.

"It was a bizarre, frightening time," said epidemiologist Frits van Griensven. The helplessness was profound, not just for the patients, but for the doctors and nurses on the front lines who could only bear witness to the devastation.

"We stood by, watched, and our patients died. There was nothing we could do."

Science and Solidarity: The Amsterdam Cohort Studies

In the face of this crisis, a unique and powerful alliance was forged. In 1984, Coutinho and van Griensven, along with community organizations like the COC and the Schorerstichting, launched the Amsterdam Cohort Studies (ACS). The goal was to understand this new virus: how it spread, how it progressed, and who was at risk.

The response from the gay community was an act of incredible bravery. Over 700 men volunteered, agreeing to give blood samples every three months and answer deeply personal questions about their lives and sexual habits. They were putting their trust in science at a time of immense fear and stigma, hoping to find answers that could save their friends, their lovers, and themselves.

The initial findings were grim. Blood samples from 1984 revealed that nearly a third of the participants were already infected with what would be identified as HIV. The study became a chronicle of the epidemic's brutal march, tracking in real-time as healthy men developed AIDS and died. Yet, this painful data was crucial. The ACS provided invaluable insights into the virus, contributing to the global scientific effort that would eventually lead to life-saving treatments.

Legacy of the Fight

For over a decade, there was no cure. The community organized, creating support networks like Buddyzorg to care for the sick and dying. They marched and protested, fighting against discrimination and demanding government action. It wasn't until 1996, with the arrival of combination therapy, that the tide finally began to turn. HIV was transformed from a death sentence into a manageable chronic condition.

Today, the Netherlands remembers the thousands of lives lost. The Aidsmonument on the Piet Heinkade in Amsterdam stands as a testament to a generation of men who were taken too soon. The story of the early AIDS crisis is not just one of tragedy and loss; it is a powerful history of a community that, when faced with annihilation, responded with courage, solidarity, and a defiant fight for life.

Based on this article in Parool